65 Years Ago: First Factory Rollout of the X-15 Hypersonic Rocket Plane

On Oct. 15, 1958, the first X-15 hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft rolled out of its factory. A joint project among NASA, the U.S. Air Force, and the U.S. Navy, the X-15 greatly expanded our knowledge of flight at speeds exceeding Mach 6 and altitudes above 250,000 feet. Between 1959 and 1968, 12 pilots completed 199 missions, […]

On Oct. 15, 1958, the first X-15 hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft rolled out of its factory. A joint project among NASA, the U.S. Air Force, and the U.S. Navy, the X-15 greatly expanded our knowledge of flight at speeds exceeding Mach 6 and altitudes above 250,000 feet. Between 1959 and 1968, 12 pilots completed 199 missions, achieving ever-higher speeds and altitudes while gathering data on the aerodynamic and thermal performance of the aircraft flying to the edge of space and beyond and returning to Earth. The X-15 served as a platform for a series of experiments studying the unique hypersonic environment. The program experienced several mishaps and one fatal crash. Knowledge gained during X-15 missions influenced the development of future programs such as the space shuttle.

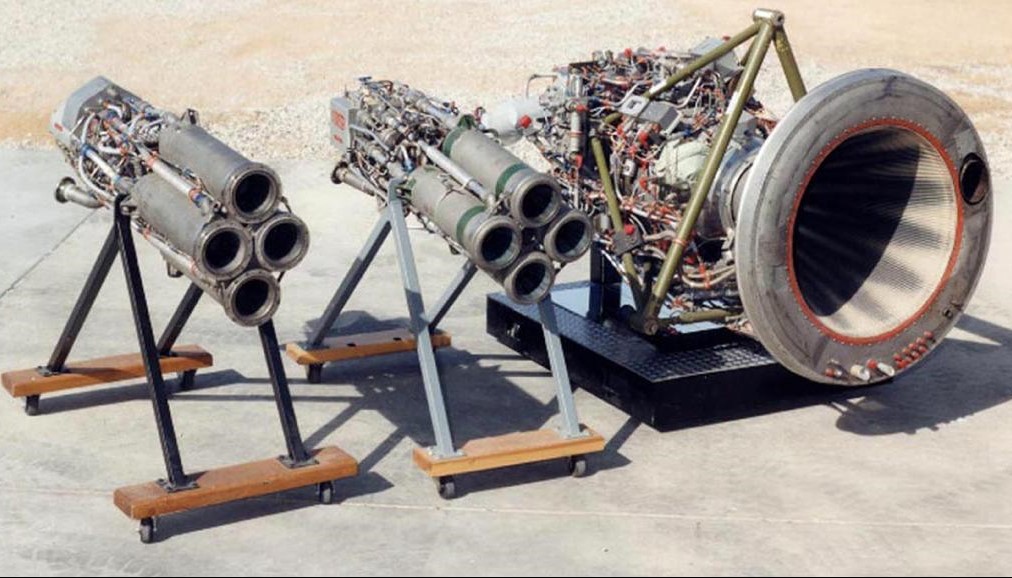

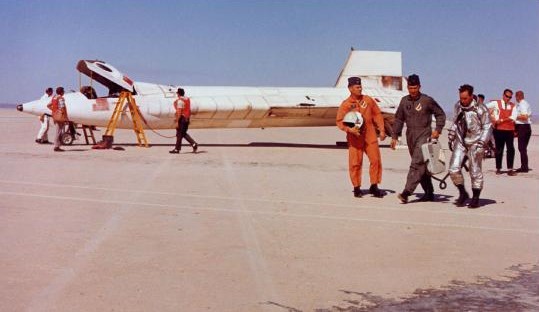

Left: Rollout of the first X-15 hypersonic research rocket plane at the North American Aviation facility in Los Angeles. Middle: North American pilot A. Scott Crossfield poses in front of the X-15-1. Right: Rear view of the X-15-1, showing the twin XLR-11 rocket engines used on early test flights.

The origins of the X-15 date to 1952, when the Committee on Aerodynamics of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) adopted a resolution to expand their research portfolio to study flight up to altitudes between 12 and 50 miles and Mach numbers between 4 and 10. The Air Force and Navy agreed and conducted joint feasibility studies at NACA’s field centers. On Dec. 30, 1954, the U.S. Air Force released a Request for Proposals (RPF) for aerospace firms to bid on building the experimental hypersonic aircraft. Four companies submitted proposals with the Air Force selecting North American Aviation, Los Angeles, as the winning bid on Sept. 30, 1955, awarding the contract in November. The Air Force held a separate competition for the aircraft’s XLR-99 rocket engine, a 57,000-pound throttleable single-chamber engine. The process began with release of the RFP on Feb. 4, 1955, and selection in February 1956 of the Reaction Motors Division of Thiokol Chemical Corporation. Delays in the development of the XLR-99 engine required North American to rely on a pair of four-nozzle XLR-11 engines, similar to the one that powered the X-1 on its historic sound-barrier breaking flight in 1947. Providing only 16,000 pounds of thrust, this left the X-15 significantly underpowered for the first 17 months of test flights. On Oct. 1, 1958, the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) incorporated the NACA centers and inherited the X-15 project, just two weeks before rollout from the factory of the first flight article.

Left: Crowds gather to admire the first X-15 after its rollout from the North American Aviation plant in Los Angeles. Right: Workers at Edwards Air Force Base in California lift the first X-15 off its delivery truck.

On Oct. 15, 1958, the rollout of the first of the three aircraft took place with some fanfare at North American’s Los Angeles facility. Vice President Richard M. Nixon and news media attended the festivities, as did North American X-15 project manager Harrison A. “Stormy” Storms and several of the early X-15 pilots. After the conclusion of the ceremonies, workers wrapped the aircraft, placed it on a flatbed truck, and drove it overnight to the High Speed Flight Station, today NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center, at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in California’s Mojave Desert. Even before this first aircraft took to the skies, North American rolled out X-15-2 on Feb. 27, 1959. The third aircraft, equipped with the LR-99 engine and a more advanced adaptive flight control system, rounded out the small fleet in 1960.

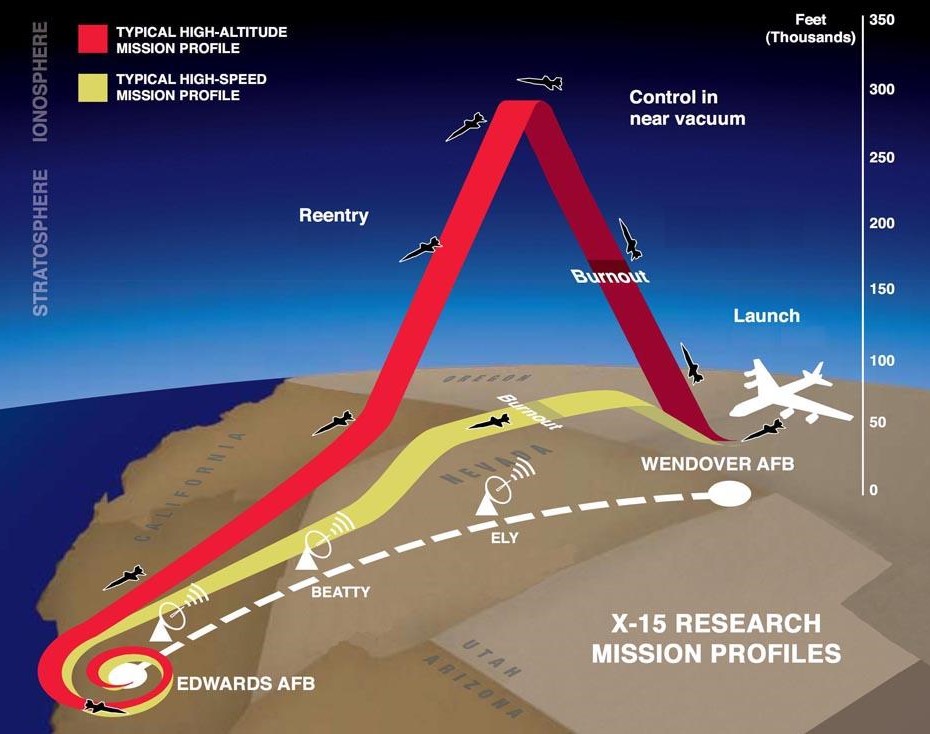

Left: Diagram showing the two main profiles used by the X-15, either for altitude or speed. Right: The twin XLR-11 engines, left, and the more powerful XLR-99 engine used to power the X-15.

Like earlier X-planes, a carrier aircraft, in this case two modified B-52 Stratofortresses, released the 34,000-pound X-15 at an altitude of 45,000 feet to conserve its fuel for the research mission. Flights took place within the High Range, extending from Wendover AFB in Utah to the Rogers Dry Lake landing zone adjacent to Edwards AFB, with emergency landing zones along the way. Typical missions lasted eight to 12 minutes and followed either a high-altitude or a high-speed profile following launch from the B-52 and ignition of the rocket engine. After burnout of the engine, the pilot guided the aircraft to an unpowered landing on the lakebed runway. To withstand the high temperatures during hypersonic flight and reentry, the X-15’s outer skin consisted of a then-new nickel-chrome alloy called Inconel-X. Because traditional aerodynamic surfaces used for flight control while in the atmosphere do not work in the near vacuum of space, the X-15 used its Ballistic Control System thrusters for attitude control while flying outside the atmosphere. North American pilot A. Scott Crossfield had the primary responsibility for carrying out the initial test flights of the X-15 before handover to NASA and the Air Force.

Left: With North American Aviation pilot A. Scott Crossfield in the cockpit, the first captive flight of the X-15-1 rocket plane takes off under the wing of its B-52 Stratofortress carrier aircraft. Right: Seconds after release from the B-52, with Crossfield at the controls, the X-15-1 begins its first unpowered glide flight.

With Crossfield at the controls of X-15-1, the first captive flight during which the X-15 remained attached to the B-52’s wing, took place on March 10, 1959. Crossfield completed the first unpowered glide flight of an X-15 on June 8, the flight lasting just five minutes. On Sept. 17, at the controls of X-15-2, Crossfield completed the first powered flight of an X-15, reaching a speed of Mach 2.11 and an altitude of 52,000 feet. Overcoming a few hardware problems, he brought the aircraft to a successful landing after a flight lasting nine minutes. During 12 more flights, Crossfield expanded the aircraft’s flight envelope to Mach 2.97 and 88,116 feet while gathering important data on its flying characteristics. All except his last three flights used the lower thrust LR-11 engines, limiting the aircraft’s speed and altitude. The last three used the powerful LR-99 engine, the one the aircraft was designed for. Crossfield’s 14th flight on Dec. 6, 1960, marked the end of North American’s contracted testing program, turning the X-15 over to the Air Force and NASA.

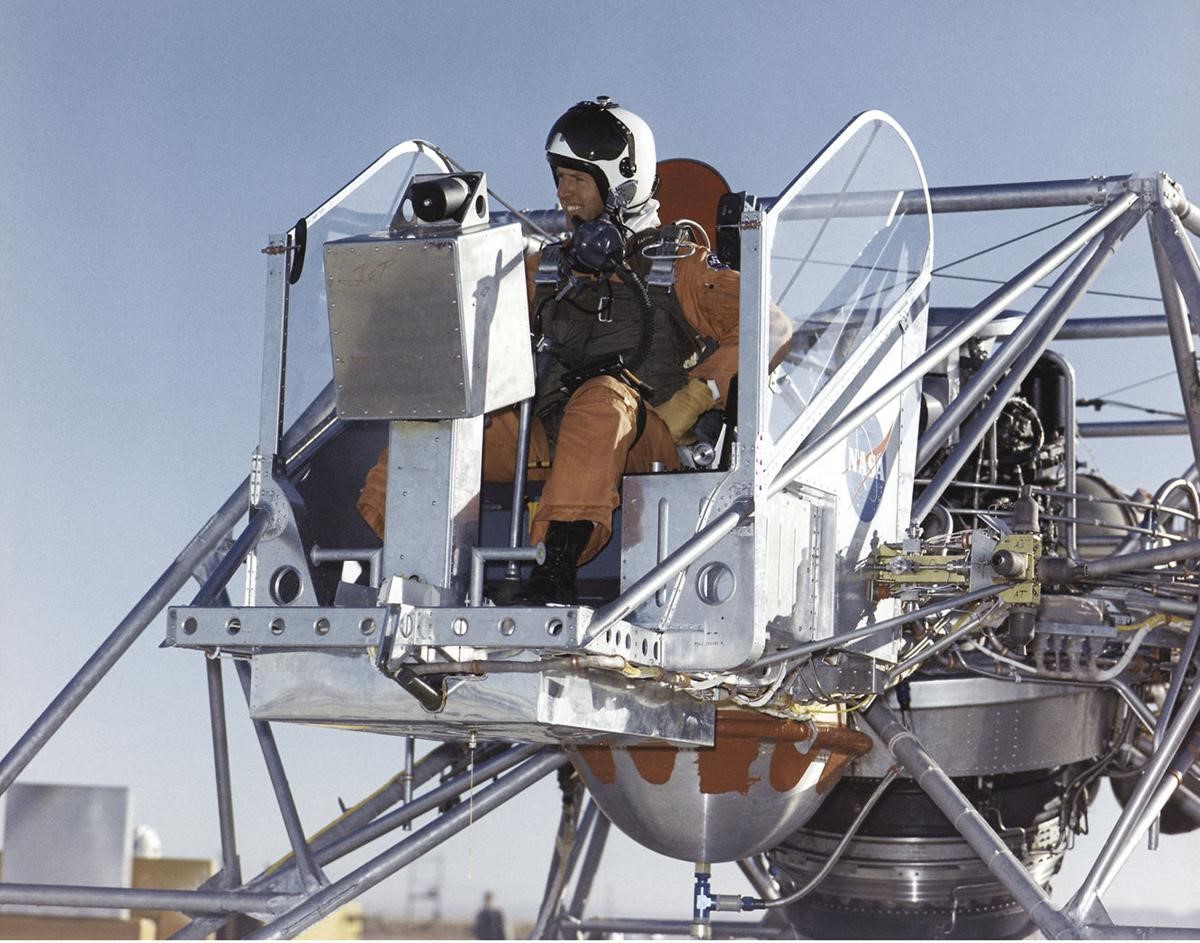

Left: Chief NASA X-15 pilot Joseph A. “Joe” Walker launches from the B-52 carrier aircraft to begin his first flight. Middle: Walker following his altitude record-setting flight in 1963. Right: Walker at the controls of the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle in 1964.

On March 25, 1960, NASA’s chief X-15 pilot Joseph A. “Joe” Walker, completed the agency’s first flight aboard X-15-1. Walker, one of five NASA pilots to fly the X-15, completed 25 flights aboard the aircraft. On May 12, 1960, Walker took X-15-1 above Mach 3 for the first time. On two of his flights, Walker exceeded the Von Karman line, the internationally recognized boundary of space of 100 kilometers, or 62 miles, earning him astronaut wings. On a third flight, he flew above 50 miles, the altitude the Air Force considered the boundary of space. By that standard, 13 flights by eight X-15 pilots qualified them for Air Force astronaut wings. On Walker’s final flight on Aug. 22, 1963, he flew X-15-3 to an altitude of 354,200 feet, or 67.1 miles, the highest achieved in the X-15 program, and a record for piloted aircraft that stood until surpassed during the final flight of SpaceShipOne on Oct. 4, 2004. After leaving the X-15 program, Walker conducted 35 test flights of the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) between 1964 and 1966, the precursor to the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle that Apollo commanders used to simulate the final several hundred feet of the Lunar Module’s descent to the lunar surface. Tragically, Walker died in a mid-air collision on June 8, 1966, when his F-104 Starfighter struck an XB-70 Valkyrie during a demonstration exercise.

Left: NASA X-15 pilot John B. “Jack” McKay poses with X-15-3 after a mission. Middle: Rollout of X-15A-2 in 1964, repaired and modified following a landing mishap.

The second NASA X-15 pilot, John B. “Jack” McKay completed 29 flights, the most of any NASA pilot. He achieved a maximum speed of Mach 5.65 and reached an altitude of 295,600 feet, qualifying him for Air Force astronaut wings. On Nov. 9, 1962, he suffered serious injuries during a landing mishap on his seventh mission but recovered to make 22 more flights. Engineers at North American not only repaired the damaged X-15-2 but redesignated it as X-15A-2. They extended its fuselage by more than two feet and added two external fuel tanks to enable longer engine burns. McKay made another emergency landing on his 25th flight on May 6, 1966, when the X-15-1’s LR-99 engine shut down prematurely. The aircraft did not incur any damage and McKay suffered no injuries.

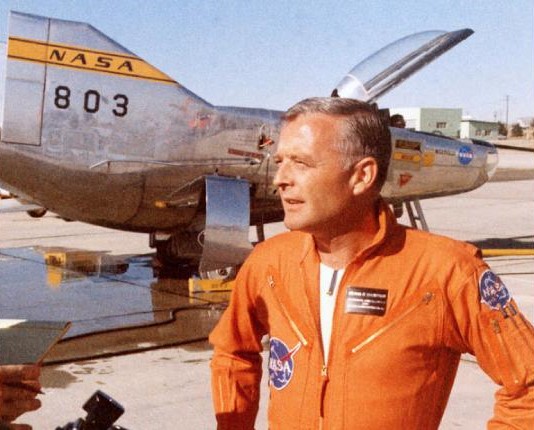

Left: NASA pilot Neil A. Armstrong stands next to an X-15. Middle: Armstrong sits in Gemini VIII prior to liftoff. Right: Armstrong in the Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle following his historic Moon walk.

Neil A. Armstrong joined NACA as an experimental test pilot in January 1952, and gained experience flying the X-1B supersonic rocket plane. NACA selected him as its third X-15 pilot, and he flew the aircraft seven times. After his first two checkout flights in December 1960, Armstrong spent a year as a consultant on the X-20 Dyna-Soar program before returning to fly his remaining five X-15 missions. Because he helped to develop the adaptive flight control system, on Dec. 20, 1961, Armstrong completed the first flight of X-15-3, rebuilt after an explosion in June 1960 of the LR-99 engine on a test stand destroyed the back of the aircraft. On his sixth flight on April 20, 1962, while trying to maintain a constant g-load during reentry, the aircraft’s attitude caused it to skip out of the atmosphere. This resulted in an overshoot of the landing zone, requiring a high-altitude U-turn, with Armstrong just barely reaching the lakebed runway. Armstrong left the X-15 program when NASA selected him as an astronaut on Sept. 17, 1962. In March 1966, as the Gemini VIII Command Pilot, he executed the first docking in space and then guided the spacecraft back to Earth after the first in-space emergency. On July 20, 1969, during Apollo 11, Armstrong took humanity’s first step on the Moon.

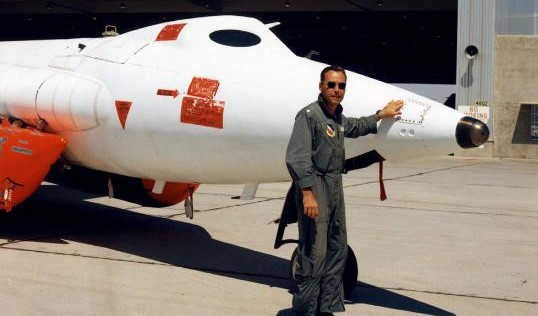

Left: NASA pilot Milton O. Thompson poses in front of X-15-3. Right: Thompson poses in front of the M2-F2 lifting body aircraft after his first flight in 1966.

In June 1963, NASA selected Milton O. “Milt” Thompson as an X-15 pilot, and he completed 14 flights. Although he achieved a maximum speed of Mach 5.48 and reached 214,100 feet, more than half his flights remained at relatively low altitude but high speed to gather data on the effects of high temperatures on the skin of the X-15. Thompson transferred to test fly the experimental M2-F2 lifting body aircraft before giving up flying to manage advanced research projects for NASA, including influencing the design of the space shuttle orbiter. His X-15 experience convinced him that the orbiter did not need jet engines to assist in the landing. Thompson served as the chief engineer at NASA’s Dryden Flight Reseach Center, now Armstrong Flight Research Center, from 1975 until his death in 1993.

Left: NASA pilot William “Bill” Dana poses in front of X-15-3. Right: Dana after the final rocket powered aircraft flight, aboard the X-24B, at Edwards Air Force Base in 1975.

In May 1965, NASA selected William “Bill” H. Dana, already involved in the program as a chase pilot and simulation engineer, to backfill Thompson as an X-15 pilot. Dana completed 16 flights including what turned out to be the final flight of the X-15 program on Oct. 24, 1968. He reached a maximum speed of Mach 5.53 and an altitude of 306,900 feet, high enough to qualify him for Air Force astronaut wings. With the program sufficiently mature, in addition to gathering flight characteristics data, several experiments flew aboard Dana’s flights. On the last mission, Dana observed a Minuteman missile launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base. Following the end of the X-15 program, between April 1969 and December 1972, Dana piloted experimental lifting body aircraft like the HL-10 and M2-F3, and in September 1975, he flew the X-24B twice, including the final flight of a rocket-powered aircraft at Edwards. After test flying other aircraft, he served as Dryden’s chief engineer between 1993 and 1998, taking over from Thompson.

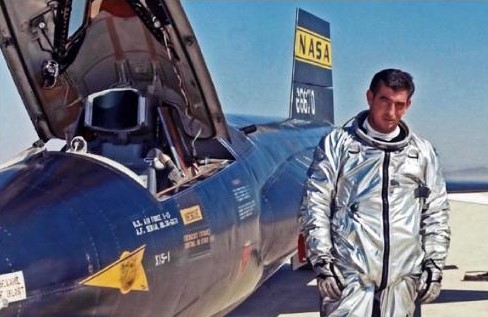

Left: U.S. Air Force pilot Robert M. White after the last flight of an X-15 with the LR-11 engines. Right: White inside the X-15 about to launch on the first flight above Mach 6.

Five U.S. Air Force and one U.S. Navy pilot made history flying the X-15. The U.S. Air Force selected Iven C. “Kinch” Kincheloe as their first X-15 pilot, but tragically he died in an aircraft accident on July 26, 1958, before making a flight. His backup, Robert M. White, stepped in as the first Air Force pilot to fly the X-15, completing 16 missions. Over the course of these missions, White’s achievements included the first flight of an X-15 above 100,000 feet, then 200,000 feet, and eventually to 314,750 feet. That earned White U.S. Air Force astronaut wings on his July 17, 1962, flight. He also broke speed records, as the first person to fly faster than Mach 4, then Mach 5, and finally reaching Mach 6.04 – more than doubling the speed record in just eight months. After leaving the X-15 program, White flew combat missions in southeast Asia, the only X-15 pilot to see active duty in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. He retired as a major general in 1981.

Left: U.S. Navy pilot Forrest S. “Pete” Petersen poses next to an X-15. Right: The B-52 carrier aircraft flies overhead to salute Petersen’s highest and fastest flight.

Left: Air Force pilot Robert A. Rushworth following a flight aboard X-15-3. Right: Unusual photograph of two B-52s preparing to launch two X-15s in November 1960 – X-15-1 prepares to taxi for Rushworth’s first flight, left, and X-15-2 for A. Scott Crossfield and the first flight of the XLR-99 rocket engine. Image credit: courtesy mach25media.com.

The pilot with the most X-15 missions, the Air Force’s Robert A. Rushworth completed 34 flights. For the first time, flight surgeons could monitor a pilot’s electrocardiogram in real time thanks to a new biomonitoring system and did so during Rushworth’s seventh flight. On his 14th flight, Rushworth reached an altitude of 285,000 feet, high enough to earn him U.S. Air Force astronaut wings. Rushworth flew his fastest flight on Dec. 5, 1963, when he reached a top speed of Mach 6.06. On June 25, on his 21st mission, Rushworth completed the first flight of X-15A-2, rebuilt and upgraded following its November 1962 crash. He piloted it to Mach 4.59, the first time the aircraft flew faster than Mach 4. On his next flight, he took the aircraft past Mach 5. On his 34th and final mission, Rushworth tested one of the significant upgrades to X-15A-2, the addition of disposable external fuel and oxidizer tanks to increase the rocket engine’s burn time. He encountered some difficulties when he jettisoned the tanks at the half-full stage, a condition that planners had not anticipated, but successfully landed the aircraft. As previously planned, Rushworth left the X-15 program five days later, attending the National War College before flying 189 combat missions in Vietnam. He retired as a major general in 1981.

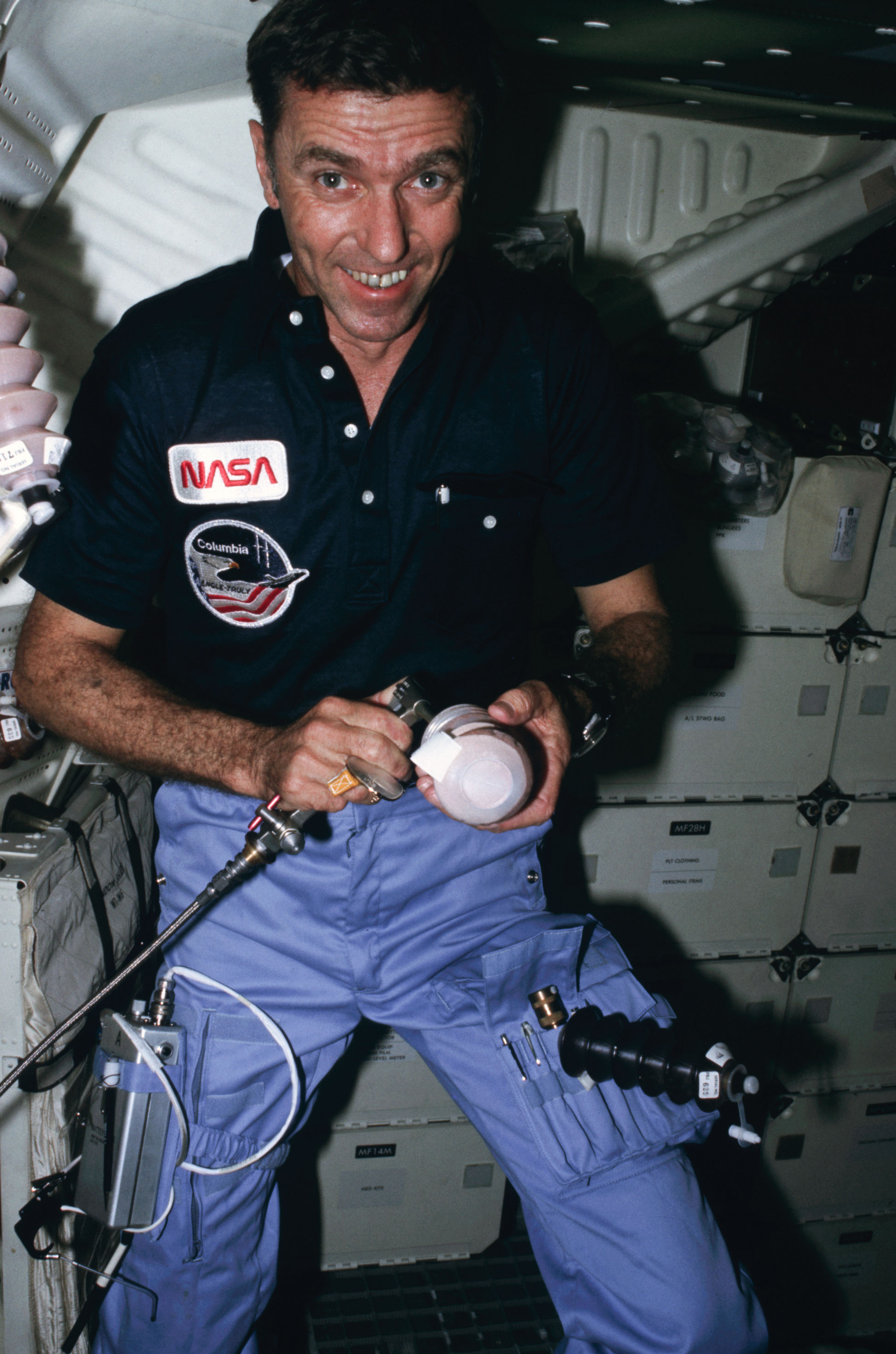

Left: Air Force pilot Joe H. Engle following a flight aboard X-15A-2. Middle: NASA astronaut Engle poses in front of space shuttle Enterprise during its first rollout in 1976. Right: Engle during Columbia’s STS-2 mission in November 1981.

Air Force pilot Joe H. Engle joined the X-15 program in June 1963, completing 16 missions. He achieved his highest speed, Mach 5.71, on his 10th flight, and earned his U.S. Air Force astronaut wings at 33 years of age, the youngest X-15 pilot to do so, on his 14th flight. Within less than four months, Engle surpassed the 50-mile mark two more times on his final two X-15 flights in August and October 1965. Engle left the X-15 program when NASA selected him as an astronaut on April 4, 1966. Putting his X-15 experience to good use, he commanded two of the five Approach and Landing Tests with space shuttle Enterprise in 1977. In 1982, he commanded STS-2, the second orbital flight of Columbia, and in 1985 he commanded STS-51I, the sixth flight of Discovery. Comparing the X-15 and the space shuttle, the only person to have piloted both said, “From a pilot-task standpoint, the entry and landing are very similar, performance wise. You fly roughly the same glide speed and the same glide slope angle. The float and touchdown were very similar.” Engle retired from NASA and the Air Force as a major general in 1986 but remained active in an advisory capacity into the 2010s.

Left: Air Force pilot William J. “Pete” Knight poses with X-15A-2 with its unusual white outer paint over an ablative coating. Right: Knight, right, following his speed record-setting flight in October 1967.

The Air Force selected William J. “Pete” Knight as an X-15 pilot in 1965, and he completed 16 flights in two years. On his eighth flight on Nov. 18, 1966, Knight took X-15A-2 to above Mach 6, with the fully fueled external tanks operating as expected. In an attempt to protect the X-15’s skin during sustained flight at Mach 6, or proposed future flights at Mach 7 and 8, engineers coated X-15A-2 with an ablative material. Since the color of the material resembled the pink of a pencil eraser, workers painted it a gleaming white. On Oct. 3, 1967, Knight flew X-15A-2, with fully fueled external tanks, to an unofficial speed record of Mach 6.70, or 4,520 miles per hour, for a piloted winged vehicle. The mark stood until surpassed during the reentry of space shuttle Columbia on April 14, 1981. While the flight appeared to have gone well, hypersonic shock waves, especially around a model scramjet attached to the bottom rear of the aircraft, caused such heating that it burned through the ablative material, exposing the skin of the aircraft to 2,400 degrees, twice its design limit. Postflight inspection revealed significant damage to the aircraft that would have ended catastrophically had the heating continued for a few more seconds. A previous flight to Mach 6.33 showed similar, although less, severe damage, but engineers did not consider it as a warning sign. Due to the damage, X-15A-2 never flew again. In 2003, space shuttle Columbia suffered similar burn, caused by damage to its thermal protection system, leading to loss of the vehicle and its seven-member crew. When the X-15 program ended at the end of 1968, Knight returned to active duty, flying 253 combat missions in Vietnam in 1969 and 1970. He eventually returned to Edwards as its vice commander before retiring in 1982 and entering politics.

Left: Michael J. Adams, left, selected in the first group of astronauts for the U.S. Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory in 1965. Right: Adams following a mission aboard X-15-1.

The U.S. Air Force first selected Michael J. Adams as an astronaut for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program in November 1965 before transferring him to the X-15 program in July 1966 as its 12th and final pilot. He flew the X-15 seven times and on his third flight reached his highest speed of Mach 5.59. Adams took off on his seventh flight on Nov. 15, 1967, a mission using X-15-3 with its advanced flight control system, to reach 250,000 feet and Mach 6 to conduct several experiments. After overshooting to a peak altitude of 266,000 feet and beginning the descent but sill well outside the atmosphere, the X-15-3 entered into a hypersonic spin traveling at more than 3,000 miles per hour, at one point flying tail first. Adams and the aircraft’s systems recovered from the spin, but now the aircraft began serious pitch oscillations as it continued to fall. At 62,000 feet, the g-loads from the oscillations overcame the structural limits of the aircraft and it broke apart. The X-15-3 crashed, killing Adams. The accident investigation identified proximate causes as a short-circuit from one of the experiments that had not been tested at low atmospheric pressures or high temperatures, causing both the aircraft’s computer and its flight control system to repeatedly fail. Adams became distracted and did not realize his aircraft’s attitude was increasingly off nominal. In addition, an attitude indicator switch had been set at the wrong setting, providing Adams with confusing information. Telemetry to the ground did not include attitude information, so controllers did not know the problems Adams faced and could not provide any helpful direction. Adams may have suffered from vertigo, a condition for which he had previously tested positive, a fact not known to his flight surgeon. Two major changes from the accident included adding attitude information to the telemetry and ensuring that all pilots received thorough vestibular screening to identify cases of vertigo. With the loss of X-15-3 and the retirement of the damaged X-15A-2 following Knight’s October flight, only one aircraft, the original X-15-1, remained to close out the program until funding ran out in December 1968. The Air Force posthumously honored Adams with astronaut wings.

The Edwards Air Force Base ground crew poses in front of the B-52 with X-15-1 mounted under its wing during a rare snowstorm that thwarted a final attempt at a 200th flight.

NASA pilot Dana flew what turned out to be the 199th and final X-15 mission on Oct. 24, 1968. Managers tried to fly a 200th mission before funding ran out on Dec. 31. Eight attempts between Nov. 27 and Dec. 20 for Air Force pilot Knight to take X-15-1 on a final mission failed for a variety of reasons. Due to the delays, the initial mission plan of flying to 250,000 feet at Mach 4.9 in an attempt to visualize a missile launch from Vandenberg AFB had to change to a more modest altitude goal of 162,000 feet and reduced speed of Mach 3.9 to test a new experiment. On Dec. 20, with Knight suited up and ready to board the X-15, a rare snowstorm put an end to any plans to fly, and so the program ended. The next morning, on the other side of the continent, a Saturn V lifted off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida to take Apollo 8 astronauts on the first voyage to the Moon. Seven months later, former NASA X-15 pilot Armstrong took humanity’s first steps on the Moon.

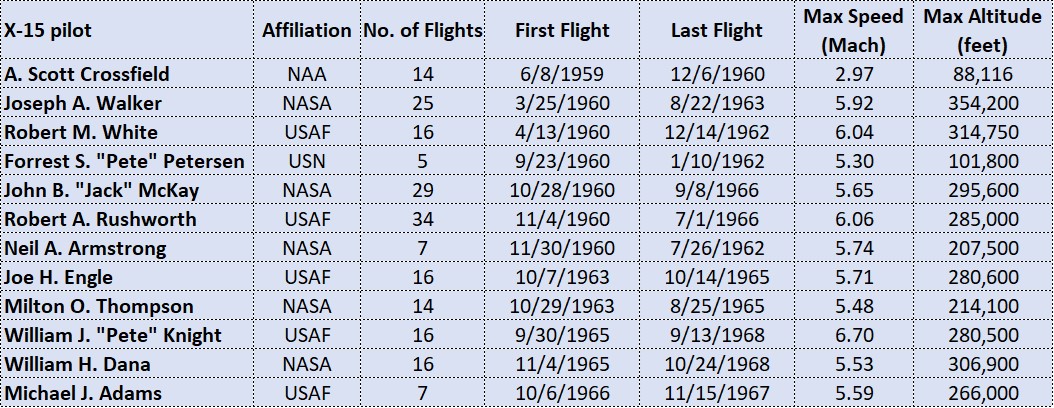

Summary of X-15 pilots’ accomplishments.

A grateful nation recognized the accomplishments of the X-15 pilots. On Nov. 28, 1961, in a White House ceremony President John F. Kennedy presented Crossfield, Walker, and White with the Harmon International Trophy for Aviators. On July 18, 1962, President Kennedy presented the prestigious Robert J. Collier Trophy to Crossfield, Walker, White, and Petersen for their pioneering hypersonic flights. On Dec. 3, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented the Harmon Trophy to Knight for his Mach 6.70 record-setting flight.

Left: President John F. Kennedy, left, presents the Harmon Trophy to X-15 pilots A. Scott Crossfield of North American Aviation, Joseph A. Walker of NASA, and Robert White of the U.S. Air Force. Middle: President Kennedy presents the Collier Trophy to X-15 pilots Crossfield, White, Walker, and Forrest S. Petersen of the U.S. Navy. Right: President Lyndon B. Johnson presents the Harmon Trophy to U.S. Air Force X-15 pilot William J. “Pete” Knight.

Left: The X-15-1 as it looked in the Milestones of Flight exhibit at the Smithsonian Institute’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Image credit: courtesy National Air and Space Museum. Middle: The X-15A-2 on display at the National Museum of the Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (AFB), in Dayton, Ohio. Image credit: courtesy National Museum of the Air Force. Right: A replica of the X-15-3 as it looked on display in 1997 outside the entrance to NASA’s Dryden, now Armstrong, Flight Research Center at Edwards AFB.

Following the end of the program, the two surviving X-15 aircraft found permanent homes in prestigious museums. The X-15-1 arrived at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., in June 1969. When the new National Air and Space Museum opened in July 1976, the X-15-1 found a place of prominence in the Milestones of Flight exhibit. In 2019, curators placed it in temporary storage while the museum undergoes a major renovation. The X-15A-2 went on display at the Air Force Museum, now the National Museum of the Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, in Dayton, Ohio, where it still resides. Although the third aircraft was lost in a crash, North American built replica of X-15-3 that was mounted outside the entrance to Dryden in 1995. Damage from winds required its removal and refurbishment, and it is currently in storage at Armstrong.

What's Your Reaction?