A Langley Intern Traveled 1,340 Miles to View a Total Solar Eclipse. Here’s What She Saw.

Emma Friedman, an Office of Communications intern at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, understood that the total solar eclipse on April 8th, 2024, was an out-of-this-world opportunity she couldn’t miss. Equipped with the proper eye protection, I traveled over one thousand miles to Dallas, Texas, to be in the eclipse’s path of totality. […]

A Langley Intern Traveled 1,340 Miles to View a Total Solar Eclipse. Here’s What She Saw.

Emma Friedman, an Office of Communications intern at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, understood that the total solar eclipse on April 8th, 2024, was an out-of-this-world opportunity she couldn’t miss.

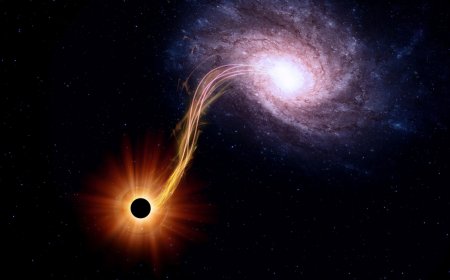

Equipped with the proper eye protection, I traveled over one thousand miles to Dallas, Texas, to be in the eclipse’s path of totality. As I got situated in a park near the city, I was excited—I’d read books and seen photos of what an eclipse looked like and knew what to expect, but I also knew that seeing it in person would be something greater than fiction. Slowly but surely, the Moon took more and more “bites” out of the sun, until I saw the last little peek of light before the darkness; this is known as the “diamond ring effect.”

Before I had time to process any of it, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. A silence fell across the park—even the birds stopped chirping—and I held my breath. All you could hear was the rustling of branches. What was a warm spring day was now a cold, dark dusk. It felt like the world had flipped on its head—first slowly, and then all at once. What the Sun had just seconds before lit was now a black void. The glow I saw around the Sun was its outer atmosphere, known as the corona. It was a moving sight, but why did I travel so far to experience it? Surely a viewing of a total eclipse was not in need of a plane ride.

It’s actually more complicated than simply waiting for the Moon to drift in front of the Sun. You have to be in the right place at the right time in a region called the “path of totality.”

As a Maryland local, seeing a total solar eclipse from my home would be impossible during this eclipse. Despite eclipses being relatively common, it is a bit more challenging to see the Moon totally block out our Sun.

I spoke to Atmospheric Scientist and expert, Marilé Colón Robles, about the so-called “eclipse chasing” people like me took part in.

“Solar eclipses happen every eighteen months or so, so they are pretty common. To see a total solar eclipse is more challenging because a limited amount of the Earth’s surface is in the path of totality at any given time. Because the world is mostly made up of oceans, your chances of seeing a total eclipse from where you live is small. If, by chance, a total eclipse is happening near you, it’s best to travel to it.”

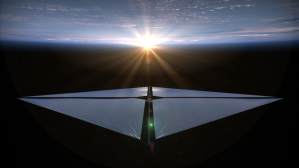

One team from NASA Langley did something similar by traveling to Houlton, Maine, to broadcast the eclipse in the path of totality. The broadcast showcases the moments before, during, and after the total solar eclipse. Another team of researchers from NASA Langley traveled to Fort Drum, N.Y., also located in the path of totality, to study changes in the weather during the total solar eclipse using a specially modified drone flying at 10,000 feet.

You can see my time lapse of the total solar eclipse below. Needless to say, the plane ride was worth it, and I was fortunate to enjoy one of the most cinematic and humbling phenomena that an Earthling can experience.

April 8th was the last total solar eclipse to cross the U.S. for another 20 years. You can watch NASA’s broadcast of the eclipse here.

Share

Details

Related Terms

What's Your Reaction?